Crush by Richard Siken might be my favorite collection of poems of all time. As an English major, I have read poem after poem after poem and so on. Nothing has ever made me feel anything close to what Siken’s writing does.

Some might say that Crush is a book written about love. But I guess that depends on your definition of love—A tangled, gnawed mess of happiness and warmth and drinking-a-cup-of-coffee-in-bed and hate and fear and pain and why-won’t-they-text-me-back and violence and blood and sex and conversation and this-song-is-for-you and poetry.

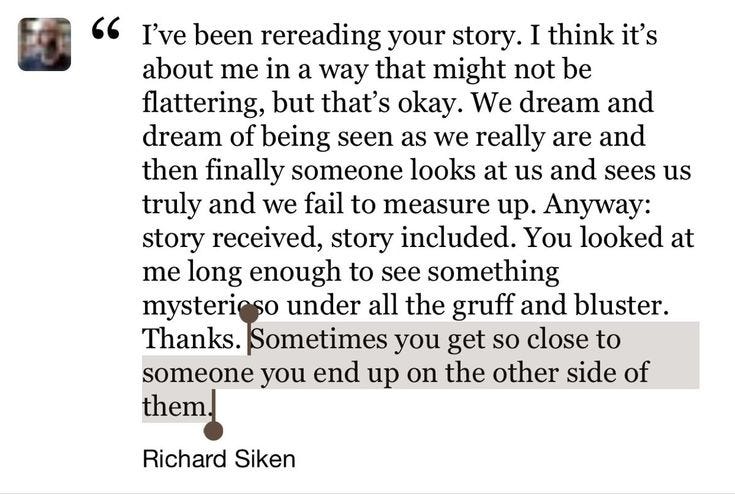

Siken writes with a kind of fevered desperation, like he’s carving out pieces of his psyche and splattering them on the page. The poems move quickly, breathlessly, switching from tender moments to gut-punching realizations, reflecting the nonsensical, chaotic thoughts of someone consumed by love.

With each line, Crush brings us closer to love’s paradox: it completes and dismantles, a ritual that leaves us exalted yet broken. Siken’s poems don’t offer gentle love; they demand surrender.

“We pull our boots on with both hands

but we can't punch ourselves awake and all I can do

is stand on the curb and say ‘Sorry

about the blood in your mouth. I wish it was mine.’

I couldn't get the boy to kill me, but I wore his jacket for the longest time.”

The way Siken writes is filthy, and dirty, and grimy. His poems wrap their hands around your neck and squeeze, grab you by the collar and pull you in and make you listen. He taps into something almost primal—love stripped down to its core, without its more “acceptable,” sugarcoated layers. Its messy and fractured, dancing between devotion and destruction.

His poem, “Litany in which Certain Things are Crossed Out,” is genuinely the most beautiful, poignant thing ever written, in my humble opinion. I read it aloud at least three times a week (seriously, just ask my poor roommate), because it sounds best in spoken word.

The poem unfolds almost like a monologue or an unfiltered confession, Siken letting us glimpse the messy aftermath of a love that’s left him bruised, questioning, and reaching for something he can’t quite name.

“Here is the repeated image of the lover destroyed.

Crossed out.

Clumsy hands in a dark room. Crossed out. There is something

underneath the floorboards.Crossed out. And here is the tabernacle

reconstructed.Here is the part where everyone was happy all the time and we were all

forgiven,even though we didn't deserve it.”

There is much tension between what is said and what remains unspoken. Siken acknowledges a profound desire to lay bare his love, his hurt, and his need, but he’s held back by a fear of being rejected or misunderstood. The poem wrestles with the inadequacy of language—how words seem both necessary and impossible for expressing the depths of his emotions.

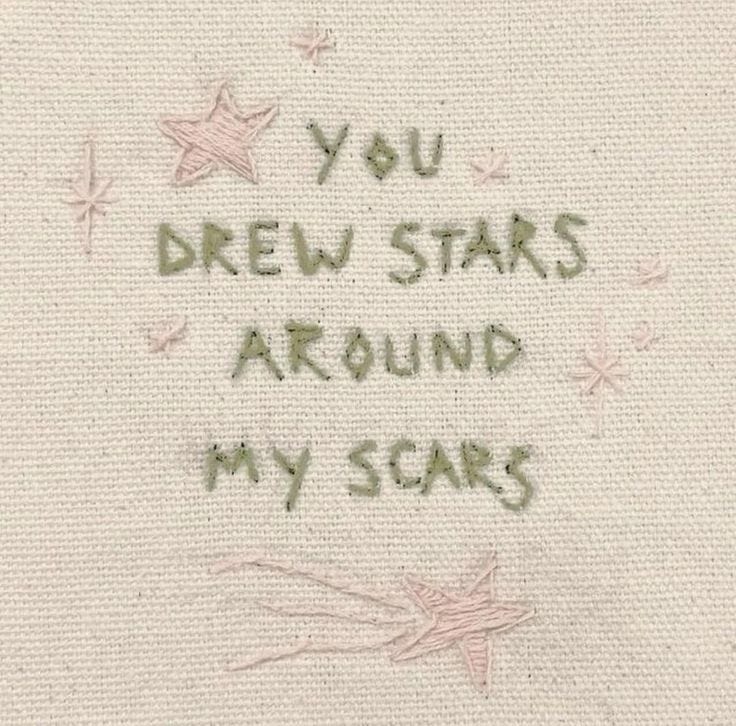

It’s not all brutality—amidst the pain, there are pockets of sunshine and wholesome hope. It’s these fleeting seconds of peace that make the chaos worthwhile, where the scars and bruises seem almost beautiful in the light. Like this line from “Scheherazade”:

“How we rolled up the carpet so we could dance, and the days were bright red,

and every time we kissed there was another apple

to slice into pieces”

Over the years, poets have compared their feelings to slicing apples, peeling oranges, dancing in the aisles of a grocery shop. We could beat around the bush forever, talk in metaphors and similes, but it all comes down to mean the same thing: I love you.

Siken writes about love not as a gentle, secure feeling but as a visceral experience that destabilizes, overwhelms, and consumes. It consumes you. It’s a force that grips you, body and soul, demanding you to wrestle with it, revel in it, and ultimately surrender to it.

It is infatuation, and obsession, and the lightest brush of your hand on my leg. It’s often one-sided, leaving one person wanting more, bruised by their need to be close and yet aware that closeness could destroy them. It’s the ultimate contradiction: the thing that completes you is the very thing that can break you.

This idea reminds me of the song “Inside Your Mind,” by The 1975. Frontman Matty Healy sings, “The back of your head is at the front of my mind/Soon I'll crack it open just to see what's inside your mind.”

This vulnerable, vulnerable lyric is reminiscent of something Siken would write, where the line between intimacy and violence is ever too thin.

It’s not enough to observe his lover or simply be near them; he needs to know what they’re thinking, dreaming, and feeling. The violent image of “cracking open” the mind is akin to the kind of obsessive love in Crush, where the speaker yearns to cross boundaries and inhabit the other person’s life so fully that their individuality almost collapses.

Love and violence become two sides of the same coin in Crush. There’s something inherently dangerous about love because it requires a surrender of control, a willingness to be completely undone by another person.

“There are so many things I’m not allowed to tell you.

I touch myself. I dream.

Wearing your clothes or standing in the shower for over an hour, pretending

that this skin is your skin, these hands your hands.”

In this quote from “Dirty Valentine,” the speaker’s longing becomes almost invasive, manifesting as a desire to fully inhabit the other person’s identity, to dissolve the boundaries between self and other. It’s the kind of love where being close isn’t close enough—where the yearning is so overpowering that it becomes an attempt to fuse with the other person completely. Sex in Crush isn’t just physical—it becomes a way to capture the tension between wanting to merge with someone and the fear that such closeness can tear you apart.

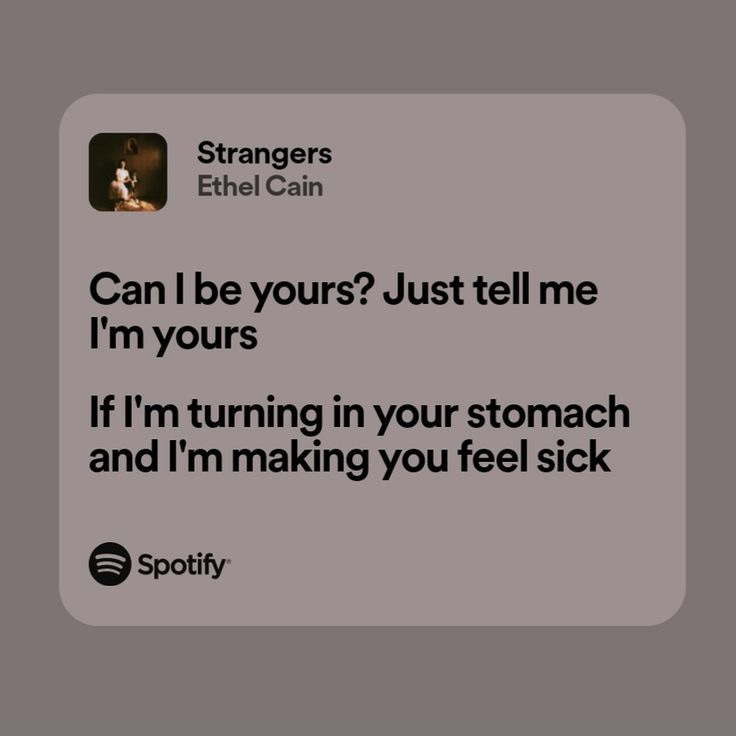

Ethel Cain (in a song coincidentally also called “Crush”) sings, “I owe you a black eye and two kisses. Tell me when you wanna come and get ‘em. I only want him if he says it first to me. I wanna, uh, him in the back of his mom’s Mercury.” She merges tenderness and violence, pleasure and pain.

Love, in Crush, is a high-wire act—dangerous and exhilarating. The willingness to be broken is part of the allure. Like Siken, Cain doesn’t shy away from the darker, more uncomfortable sides of love. Her album Preacher’s Daughter uses cannibalism and other grotesque metaphors to describe intense passion. Both artists show that the beauty of love is found as much in its ability to harm as its ability to heal.

Siken’s speaker expresses feelings that are too vast, too consuming to fit within the ordinary bounds of love. This is shown in this line from “Litany”:

“You said I could have anything I wanted, but I

just couldn't say it out loud.

Actually, you said ‘Love, for you,

is larger than the usual romantic love. It's like a religion. It's

terrifying. No one

will ever want to sleep with you.’”

This quote exposes a truth most of us feel but rarely admit—loving someone like this isn’t just intense; it’s terrifying. It’s an all-consuming devotion that borders on religious fervor. Siken undercuts the romantic ideal of connection by implying that the speaker’s love, though sacred in its own way, is too intense for traditional intimacy. It’s a love that makes others retreat because it holds nothing back and asks for everything in return.

Similarly, Frank Ocean sang in “Bad Religion,” “Unrequited love ain’t nothing but a one man cult.” Love is pouring all of your devotion into someone who may never reciprocate. You end up worshipping this idea of love, consumed by it, even though you’re the only one participating in the ritual. The pain of unreturned love becomes this private, almost sacred practice, where obsession and longing take on a life of their own.

Siken encapsulates the fragile beauty and inevitable tragedy of love at its most intense, demonstrated by another line from “Scheherazade.”

“Tell me how all this, and love too, will ruin us.

These, our bodies, possessed by light.

Tell me we'll never get used to it.”

This line is a form of surrender to the inevitable ruin that true intimacy brings. Love possesses them; it fills them with an indescribable radiance, but that intensity is also fleeting. The beauty of this line is that it shows love’s duality—its ability to lift us up, yet leave us haunted. It is a plea to keep feeling this intensely, to avoid the numbness that time or routine can bring.

Siken’s speaker invites us to live in that intensity, to stay open to being consumed and broken and ruined by love, without retreating into safety. Because, in the end, it’s that kind of raw love—love we’ll “never get used to”—that makes us feel most alive.